Over the last few months, I’ve been thinking a lot about the evidence for Christianity. Specifically, I’ve been pondering just how far the historical evidence can take us—in our own faith, and in our evangelism.

This isn’t about questioning the quality of the evidence. I’m as deeply persuaded as ever that the historical evidence for Christianity is credible and compelling. To give a brief sketch of what I mean, I usually think about this in four categories: external, internal, archaeological and bibliographical.

The external evidence test looks to non-Christian ancient historians like Josephus, Pliny, Tacitus, and Thallus. Just from these writers alone, we can conclude that Jesus existed, died on a cross under Pontius Pilate (during a strange mid-afternoon bout of darkness), was proclaimed as having risen again, gained a large number of followers who made a major impact across the Roman Empire, and was proclaimed as divine.

The internal evidence test examines the Bible itself and asks whether it’s internally consistent. Charges of contradiction can be explained by carefully applying the normal rules of reading—for example, how we harmonise different accounts of the same event. In fact, just the right amount of difference tells us we’re reading real history written with various points of emphasis, not the work of charlatans who’ve gotten together and cooked the books.

The archaeological evidence test asks whether discoveries in the ancient world match the details described in the Bible. Again and again, archaeological finds have supported the Bible’s references to real times, places and people. To take just one example, the discovery of the “Pool of Bethesda” mentioned in John 5 upheld the reliability of John’s account and ended many years of conjecture and scepticism.

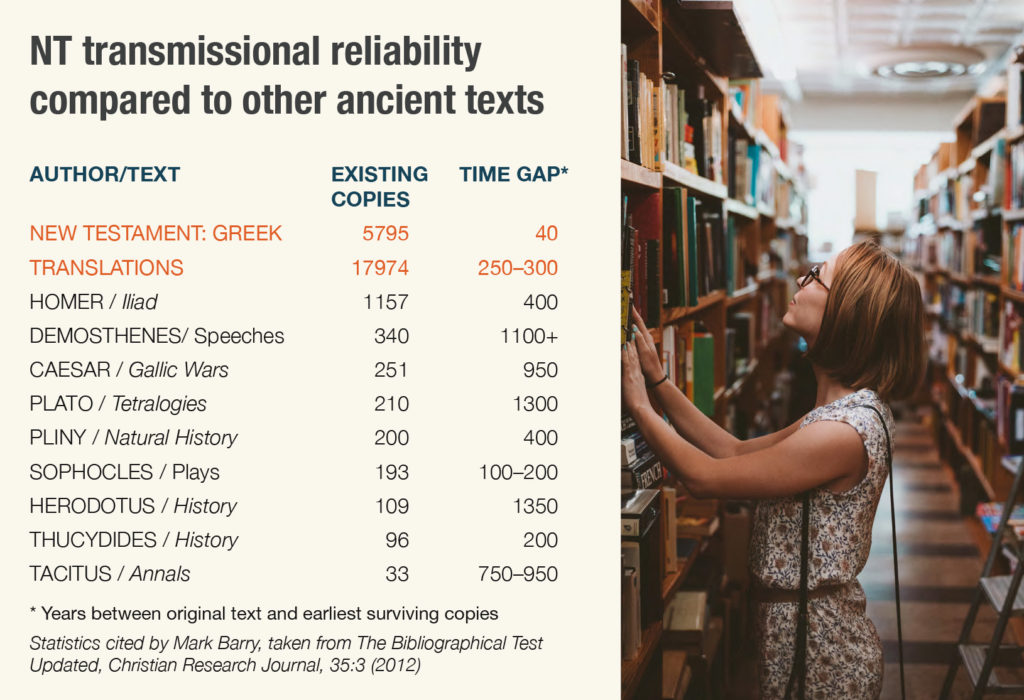

And finally, the bibliographical evidence test looks at the number of manuscript copies and the gap in time between the originals and the earliest copies. The more copies the better, as it allows for careful cross-checking; the smaller the time gap the better, as there’s less time for errors to creep in. In both cases, the Bible doesn’t just pass the test or meet the standard; it obliterates the standard and dramatically raises the bar. For example, the gold standard in ancient history is Homer’s Iliad, with 643 manuscript copies and a time gap of 500 years between the original and the earliest existing copy. When it comes to the New Testament, we have over 5,800 copies (in Greek alone!), with a time gap of somewhere between 50 and 100 years between the original and the earliest existing copy. When it comes to the reliability of ancient documents, it’s the New Testament first, daylight second.

Of course, that’s the briefest possible sketch of the evidence for the Bible, but it hints at what I (and countless other Christians) have found. (For more detail, I’d recommend Is The New Testament History? by Paul Barnett, or—humbly, and not in Paul Barnett’s league—my own The Book of Books.) Being a Christian doesn’t mean checking your brain at the door and believing the unbelievable—“blind faith” and all that nonsense. On the contrary, we have good, logical reasons for believing what we do.

But here’s the question: how far can this evidence get us? Can it sustain our faith in Jesus? Can it bring someone to faith in Jesus?

In 1 Corinthians 2:12–14, Paul writes about the essential role of the Spirit in allowing us to grasp the truth about God:

What we have received is not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit who is from God, so that we may understand what God has freely given us. This is what we speak, not in words taught us by human wisdom but in words taught by the Spirit, explaining spiritual realities with Spirit-taught words. The person without the Spirit does not accept the things that come from the Spirit of God but considers them foolishness, and cannot understand them because they are discerned only through the Spirit.

Ever sat through an evangelistic talk with a non-Christian friend and thought, “How can they not get it?!” only to have them respond, “Meh”? Ever presented the kind of evidence I described above, only to have your friend seem uninterested and unmoved? That’s because the Bible’s message is about so much more than the intellect. The heart and the emotions are intimately involved. The human desire for autonomy shapes our ability—and our willingness—to consider the evidence properly. Spiritual blindness is real (2 Corinthians 4:3–4).

Of course, God can and does open blind eyes, but he does that through the good news of Jesus (2 Corinthians 4:5–6). To put it another way: he doesn’t save people through a message about the Bible, but through a message from the Bible.

That doesn’t mean we ignore historical evidence. Far from it. Just like good foundations are indispensable to a solid home, the historical evidence for the Bible is indispensable for our evangelism and our discipleship. But just like it would be weird for me to move out of my home and set up camp underneath in the home’s foundations, it makes no sense to spend lots of time dwelling on the truth about the Bible without focusing on the Bible’s content.

We need to get the foundations in place, and we should be ready to share them with anyone who asks. But our real task is to get on with preaching the Bible’s message about the Lord Jesus Christ, crucified and risen for our sins. An earth-shattering, life-changing message with a foundation strong enough to hold it up—that’s a mighty combination.