“I have a small gaming problem I need to address.”

That wasn’t the point of our meeting, but it was bound to come up. Paul Dunn’s confession came in a central Auckland café just down the road from Scarlet City Studios, where he works as a game developer.

Gaming is a double-edged sword. Paul lights up as he describes its vast storytelling potential one moment, and the next he sheepishly admits to getting sucked further into life behind the screen than he’d like.

The former pastor and storyteller is part of a team of 20 or so artists, developers and designers – all gamers – who are creating a biblical allegory. It’s a dream job for Paul, using new technology to tell the old, old story. Both gaming and fleshing out biblical narratives equal legitimate research.

But the reason for this adventure they’re on, Paul said, is that it’s incredibly strategic. “Someone asked a philosopher, ‘How do you change a society?’ He said, ‘You tell a different story.’ It’s not about power or control – it’s the stories that shape us,” Paul said. “This is how we make sense of ourselves and our world. And that’s why we’ve chosen to tell the Bible as a story, because we believe it’s compelling and it shapes us.

“It reads us as much as we read it.”

Paul joined the studio in early 2014, bringing with him degrees in theology from Carey Baptist College and media from Massey University, and years of experience in both fields.

Although the studio was just a couple of years old at the time, the trust that set it up was born in the days of mail-order catalogues and telegrams – the Postal Sunday School Movement. Robert Laidlaw, founder of Farmers, established it 80 years ago. He was an outspoken Christian and generous backer of many evangelical endeavours, such as the Bible college that now bears his name.

The PSSM trustees seem to be as forward-thinking as Laidlaw was. Paul said that as the demand for printed Bible materials declined, they decided to pour resources into teaching the Word using contemporary media. And so the idea for The Aetherlight: Chronicles of the Resistance was born.

“We like to think of ourselves as more than a game,” said Tim Cleary, the lead world builder. He and Paul Abrahams, the lead designer, had just ducked into the café on their way to get milkshakes. (They really are living the dream.) “It’s a whole edu-tainment property that, like Narnia did for a generation that just read books, can do in a generation that isn’t content with a single screen.” Unlike most games, The Aetherlight is not an end in itself; its ultimate purpose is to get people into the Bible.

It is also not Super Mario Bros go to Nazareth. In addition to realistic visuals, narrative games have well-developed plots and characters, which involve more than a goal to be won with a bit of dexterity and strategy.

“The stories being told in games are phenomenal,” Paul said of the genre they’re contributing to. “The themes being addressed, and the way people are writing these games – it’s incredible storytelling, and there are incredible resources going into it.”

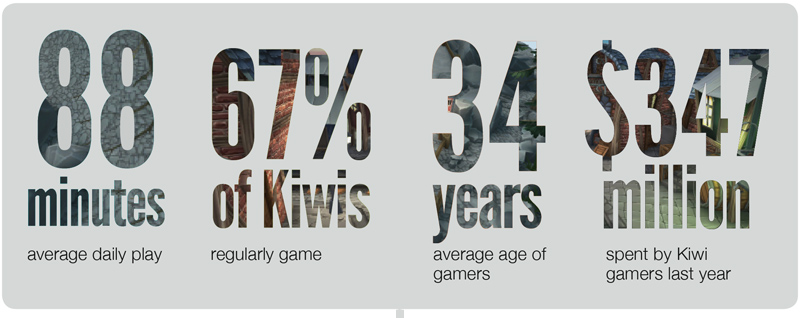

Kiwis spent $347 million on gaming in 2014, according to the latest data by the Interactive Games & Entertainment Association, published as the Digital New Zealand Report 2016. That’s nearly $80 per person, an 18% increase from the previous year. It reports $78.7 million in revenue, with 568 Kiwis employed full-time as developers.

Overseas, the industry has already surpassed the film industry’s box office revenues. Last year, games took in US$15.4 billion in the United States while cinemas generated just US$10.4 billion. For an increasing number of people, gaming is their entertainment of choice.

The average age of gamers, percentage of population playing, and time spent playing all continue to rise. Digital New Zealand says that time spent can vary from a few minutes several times a day on a hand-held device to hours a day on a computer.

The industry paints a rosy picture of itself in the Digital New Zealand report, one where games are developed to help mental health and battle memory loss. However the most mentioned reason for gaming is “to relieve boredom,” 75% play alone, and many of the remaining 25% are not physically present with those they play with.

Sexual predators, sexual content, violence, and harassment are among the most common concerns that Digital New Zealand lists for gamers and their parents.

This may not be real life, but it is real. Characters in the games take on the characteristics of the humans controlling them. In multi-player games, they interact with each other in a virtual universe that mirrors our own. But without real-life consequences, inhibitions are lower and moral choices greyer. These digital realms also exist within a reality created by storytellers with their own world views, ones often opposed to the biblical one.

“Some games deliberately and gratuitously encourage unhealthy behaviour,” Paul said. “Some would say, ‘it’s just a game.’ But if there was no context for this behaviour in which you can understand it in a wider sense, then it’s just gratuitous. If it’s just gratuitously violent, gratuitously vicious or mean or debasing, like Grand Theft Auto – pick up a hooker, take her behind the building, kill her, get points – there is nothing redeeming in that.”

These games will either warp the player’s understanding of reality – God’s reality – or enhance it.

“It’s the themes and the meaning that we draw from them which should shape our thinking in terms of ‘is this healthy for me, is this reflective of the kind of person I am or I want to be?’” Paul said. “Immersing ourselves in a fiction – whether a book or a movie or whatever – is aspirational. There’s a little bit of ‘how I want to be’ in this. There’s a little bit of how I’d like the world to be.

“… So you need to question, is what’s depicted on the screen or in this environment aspirational in an appropriate way?”

The content of the games is only one concern for gamers and their parents. There are those who find living in a fictional world more comfortable or safe or exciting than the physical world they’re part of. The games are designed to be addictive, and the most successful ones succeed in hooking people.

“There are all these games that are encapsulated, that you think you can play for a short period,” Paul said. “But you don’t. It’s an incredible game design – they’ve made them really compelling.”

Finish a book, and you’re present again. But a game doesn’t end, and it’s available 24-7 – “so I’m going to need really good internal constraints or I’m going to get lost.”

Paul’s not-universally-successful constraints include a commitment to maintaining his relationships with his wife, Kate, and their three children. This means he doesn’t sit down at the computer if there are dishes in the sink or conversations waiting to be had. He said that he and his colleagues have learned that, however well they control their gaming, there is always a real-life cost.

On one level, it helps that Paul’s children, brother, and brother’s children are gamers too. For them, gaming is an activity that builds their relationships. In fact Paul said that he and his brother weren’t close at all before they started gaming together a couple years ago.

But there are still plenty of risks, especially for children. Paul has developed a few guidelines for his, who are between the ages of 8 and 14.

• They only play games he’s played first

• He is cautious about online games – it’s an “uncontrolled window into humanity”

• Younger children don’t play in adult communities

• The degree of gore factors in; there are no first-person shooters for younger children

• Each child is allowed 4.5 computer entertainment hours a week, as and when they like, to teach them to manage time gaming

“We are unashamedly designing our game so that kids want to play it,” Paul said of The Aetherlight. “Now we have a different reason – we don’t want kids to play it so we can bankroll ourselves, we want kids to play it because we believe that they’re engaging with a story that will shape their world for eternity. So we want to make it compelling.”

Paul said that many “Christian” games he’s seen are anything but compelling, like some derivative counterparts in music and the arts that are thinly veiled tracts or sermons.

There are exceptions, however, and The Aetherlight isn’t the only one to attempt something greater. We had both read rave reviews of That Dragon, Cancer, which by all accounts has hit the mark. Ryan Green, a Christian, developed the game while he nursed his toddler son Joel through terminal cancer. Players explore the world he’s created to experience Joel’s real-life story, going through the highs and lows of sacrificially caring for a virtual child who will not survive.

Despite taking death seriously – unlike the majority of video games – and despite leading players through a story of ultimate failure, the truth in its narrative has won unlikely fans. Andy Robertson, a reviewer from secular tech magazine Wired, wrote, “The unusual decision to create a video game about this topic is matched by the inclusion of Green’s Christian faith. The risk of alienating gamers not usually receptive to mixing faith and entertainment, along with perplexing non-gamers on how a game can address such a sensitive subject, is very real.

“Play the game though, even a few early levels as I did recently, and it makes surprising emotional sense.”

Andy asked Ryan about the experience’s impact on his faith, and he replied, “when Joel was alive we were still hoping for the miracle, but I think the real challenge is to find the beauty when the story doesn’t turn out how you were hoping to write it. … Through this experience God has become bigger and more mysterious to me.”

The developers at Scarlet City Studios are also intentionally trying to reveal the nature and purpose of God through retelling his story.

“Something that’s guiding us very strongly is what we call the ‘grammar of the Gospel,’ drawing on Paul’s teaching in Corinthians about faith, hope and love,” Paul said. “If faith is identifying yourself with the story of God, and love is engaging with people in the manner that God engages within the Trinity and with humanity, hope is the expectation that God brings life out of death and new things out of nothing.

“I hope to see more games that express that.”

More information about The Aetherlight: Chronicles of the Resistance is online.